Newtown Congregational Church, Newtown, CT

June 23, 2013

(My colleague and friend, Matt Crebbin, has been going full tilt and then some since Dec. 14, 2012. Not only has he been caring for the members of his congregation, and with his wife, parenting their four active children, he's also been a strong, steady presence in the gun control movement, both here in CT and in Washington. I'll be preaching at his church through July 14 to help give him some much needed rest.)

Lately, it seems, whenever a television

show has an unhappy ending to its season finale, it’s a newsworthy

occasion. Earlier this year when Matthew

died in a car crash on Downton Abbey,

one could hear the collective “NO!” accompanied by tears, echoed on Facebook

and other social media websites. And

just two weeks ago, HBO’s Game of Thrones

shocked and disappointed most, if not all, of their fandom with more than its

share of violent and unexpected deaths.

Do

you know the word ‘fandom’? If you live

with teenage or any age fans of The Doctor or Avatar the Last Airbender or Star

Wars, you know what I’m talking about. Fandom

is a combination of the word “fanatic” and “kingdom”. Those who inhabit a fandom are passionate, from

the smallest details to the overarching narrative and themes of the object of

their focus. They engage in ‘cosplay’,

dressing up as favorite characters, paying attention, again, to every detail so

as to look as authentic as possible.

They attend huge fandom gatherings, such as Comic Con or a Star Trek convention,

form discussion groups on social media, throw thematic parties, and collect all

the toys. They are invested.

| Where great stories are massacred |

They

are especially invested in the story arc and the characters. Whenever any of us reads a novel or watches a

movie or TV show, we are invested in the outcome. How

many of you have ever felt betrayed by an author or screenwriter? What was your expectation that was dashed?

It

seems we are geared for the happy ending, or if circumstances are bad, to

expect the worst. But life is lived in

shades of charcoal, slate, and battleship.

In books, TV and movies we often seek to escape the way life is for a

more hopeful or sometimes an even darker fiction. We can put up with villains for a while, even

suffer through a few heroes’ deaths, but only because we expect the villains to

get their due and the heroes their redemptive victory in the end. We expect a certain amount of justice and

redemption, of fair play. But a great

many events in the past decade up to the past six months have given us cause to

question that narrative.

Though

it has been with us since the beginning, but especially since September 11, we

know that evil, pain, and suffering can come down on anyone, anytime,

anywhere. Some of it is within our

control but a lot of it isn’t. Sometimes

the hero wins, sometimes not. Justice is

our aim but oftentimes we miss the mark.

We’ve known for quite a while that fairytales are just that. But now as a human race it seems we have

begun to collectively wonder about the hero’s tale and does it still ring true

for us? There are times we are tempted,

like one fan of Game of Thrones who

tweeted, “I don't know if I'll ever recover from

this. No, I'm out. I quit. I'm done.”

Our

hero, the prophet Elijah, has reached this point in his relationship with the

God fandom. He’s followed God’s

storyline faithfully, he’s preached against the foreign god Baal, even ordered

the death of the priests of Baal, and it’s got him in deep trouble with Queen

Jezebel. Prophets walk a fine line

between hero and scapegoat, good-guy and outlaw. In

order to establish her cult to the god Baal, Jezebel had given orders that all

the prophets of Israel be killed; Elijah thinks he is the sole survivor of that

holocaust. Now Jezebel wants Elijah

dead.

So

Elijah assumes that he’ll never recover from this, that he’s out, he’s

quitting, he’s done. He goes out into

the desert, lies down under a tree, and asks God to take his life. And like a good Jewish mother, perhaps God is

thinking “When was the last time he ate?

Maybe he’s just hungry”, and sends an angel with some fresh bread, baked

on hot desert rocks and a jar of water to nourish Elijah not just once but

twice. The journey will be long and God

wants Elijah to live.

|

| Ferdinand Bol, Elijah Fed by an Angel, (c. 1660-1663) |

When

Elijah reaches Mt. Horeb, he’s still sticking to the hero’s script: “God, I’ve been passionate about you and your

word. Everyone else has either abandoned

you or has been killed. I’m the only one

who’s left, and now I’m about to be killed off as well.” God then tells Elijah that he is about to

pass by. Suddenly there is a violent

wind, then an earthquake, and last a fire.

Yes, earth, wind and fire.

Knowing the Jewish narrative well, Elijah expects God to show up in one

of these. But no; rather, God arrives in

a mighty silence.

We in

the United Church of Christ proclaim that God is still speaking but there are

times when it seems that God is strangely quiet. Many a faith community has been closely

following the script, passionate about the details, and yet even so, our

numbers have been steadily declining for a decade, if not two or more. The tale of our hero, Jesus, has not rung

true for some folks. Resurrection is not

easy to come by. Good people have stood

faithful during the hard times and good, and have left church for various

reasons, many of them hurtful. “I don't know if I'll ever

recover from this. No, I'm out. I quit.

I'm done.”

But none

of this is really new. Dietrich

Bonhoeffer, a young German pastor arrested for conspiring to assassinate

Hitler, wrote these words from prison in 1944:

“God as a working hypothesis in morals, politics, or science, has been

surmounted and abolished; the same thing has happened in philosophy and

religion. …Anxious souls will ask what

room there is left for God now.”

He

continues, “So our coming of age leads us to a true recognition of our

situation before God. God would have us

know that we must live as [those] who manage our lives without him. The God who is with us is the God who

forsakes us. The God who lets us live in

the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand

continually. Before God and with God we

live without God. God lets himself be

pushed out of the world onto the cross.

He is weak and powerless in the world, and that is precisely the way,

the only way, in which [God] is with us and helps us.” [i]

God

doesn’t take control of the story, despite all that we have done to mess with

God’s narrative of mercy and justice.

Rather, God works within the thwarted plot lines. God uses us to accomplish a sacred purpose,

even though our character is riddled with flaws. When the inexplicable, the unthinkable happens,

God comforts us in the faces of unexpected helpers. And, with the patience of Job, God guides us

through what we often cannot understand, even violence and meaningless

death. And time and again, it’s not our

death or another’s that we’re afraid will be meaningless but our lives or the

life of one cut short.

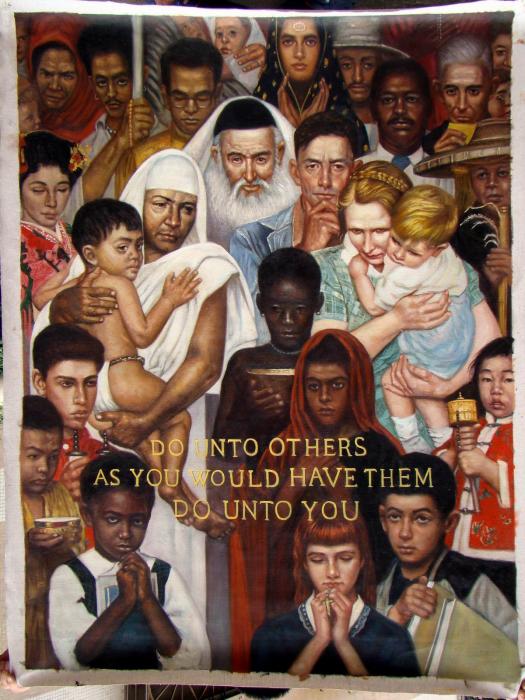

We live

in an unpredictable world, sometimes random and cruel, yet also fiercely

beautiful and fragile. We’re beginning

to realize that maybe there isn’t a script to follow so much as we’re co-authoring

a story, our story, each day. And it’s

full of contradictions, not just Jew or Greek, male or female, slave or free,

but gay and straight and bisexual, transgendered and queer. It’s extreme wealth, different kinds of

middle class, working poor, and abject poverty; it’s seeker, believer, agnostic

and atheist; not just Republican or Democrat but Independent, Libertarian, Tea

Party, Green Party, and many others. We

are many colors, many voices, all inhabiting this one earth.

|

| Norman Rockwell, The Golden Rule, 1961 |

God IS

still speaking but through us and within our stories. How invested are we in the outcome, not just

of our own stories but of the story of our neighbor and the stranger and the

enemy? The ending will take care of

itself if we are mindful of our character, our actions, decisions, and

attitudes. But it is up to us to choose

each day whether we are going to hang in there, not with the fandom but the

kingdom—God’s story of righteousness, mercy and justice.

There

are times, I am sure, when we all have been in doubt that we would recover from

a blow to our faith, when we thought we were through with church and were ready

to quit. What brought us back from that

cliffhanger? What is the story of this

church and how has it changed your life?

What choices do you need to make in order that the outcome is one of

mercy and justice? Just how invested are

you as one Body?

The

story is ongoing, and we have come this far by faith. May God grant us the courage to live out what

we pray and profess, that in the end, love will win.

Amen.